Back in 1989, when I was introduced to the Transtrend research project, the instructions were simple: “We bought data and we bought computers. Now, we hope you can do something with them.” So, that’s what we did — myself and a handful of other curious, young, slightly nerdy souls. We dove into the data. And as a result, Transtrend’s Diversified Trend Program came into being.

Our starting point was a treasure trove: up to 20 years of daily market data — open, high, low, close, volume, and open interest — across 35 different futures markets. Storing all that data required a cabinet full of large, removable disk packs. The total? Less than 250 MB. That’s less than what’s on your phone after a morning of taking cat pictures. Today, Transtrend stores more than a million times as much data, and our computing power has also grown exponentially.

So, this begs the question: are our investment decisions now exponentially more informed as well? Sadly, the answer is no. And the main reason for that is that it’s not facts, as recorded by data points, that drive markets. It’s stories.

Storytellers

We didn’t always believe this. Back then, the investment world was split into two camps: technical versus fundamental analysis. At top investment banks, using technical analysis was a firing offense. Markets were driven by supply and demand, not by trendlines or head-and-shoulder patterns. Technical analysis was dismissed as astrology for finance. On the other side, for technical analysts, the stories of fundamental analysts sounded like the Delphic oracle — mysterious and vague. For them, prices formed the only objective reality. All information was compressed into the price. We largely sympathized with that view.

But to be honest, this distinction between data and stories was never as absolute as often proclaimed. Maybe we should say this ‘only looking at prices’ is itself a story. For example, no speculative futures trader wants to take delivery of tons of soybeans. So, even the most fundamentals-averse futures trader will take first notice days and expiration dates into account. One could argue these are simply other objective data points, thus keeping the investment process purely data-driven. However, the choice to trade without taking delivery on traded contracts is a fundamental story. And data is needed to uphold that story.

Another story often maintained by traditional CTAs is: “We trade the same size in all markets.” Which means they aim to avoid overcomplicating their approach with various subjective assumptions. Sounds good, right? But what exactly does ‘same size’ mean? Does it mean the same number of contracts, so that one U.S. 30-year T-bond futures contract (representing 30 years of interest received on a $100,000 loan) is equal to one 3-month SOFR contract (representing three months of interest received on a $1,000,000 loan), one Nasdaq 100 contract, or one Micro E-mini Nasdaq 100 contract? Or is it about notional value, margin, or risk (which can be measured in various ways)? It could truly be anything!

This simple example illustrates that data alone is meaningless. It always requires interpretation. It must be given meaning and translated in some way to become useful — as part of a story. Even when that story is an extremely simple one like “We trade the same size in all markets.” However, this story itself resonates, even when it’s unclear what it actually means in terms of objectively measurable data.

Data alone is meaningless. It always requires interpretation. It must be given meaning and translated in some way to become useful — as part of a story.

Such stories can be powerful — even more powerful than data. This was something we had to learn over the years. That is, learn to accept. In our early years, we naively believed allocators would only look at the numbers: a sufficiently long track record, strong returns relative to risk — measured by Sharpe ratio or some other, more appropriate metric — and low correlation to other investments. But that’s not how money moves. Money largely follows stories.

Let’s look at LTCM and Madoff. The story is that their popularity was due to stellar performance — almost no drawdowns. But those numbers actually raised red flags for critics. The real reason investors flocked to them? Their stories. LTCM had Nobel laureates and unique knowledge. Madoff was the exclusive club for the (financial) elite. It was considered an honor to have your funds managed by them. Investors didn’t allow these stories to be ruined by data.

Money follows stories. Theranos is a more recent example. Elizabeth Holmes raised hundreds of millions of dollars by promoting the story that Theranos could revolutionize healthcare with its ability to perform over 200 blood diagnostic tests from a single drop of blood. Holmes was regarded as a star and a genius, until she was imprisoned on fraud charges. Investors love a compelling story. For that, not many facts or relevant data are needed!

One of the current success stories is AI. (No need to spell it out; that would only diminish its mystique.) Whether or not AI will ultimately deliver all its supposed benefits is irrelevant to its current market impact. Companies mention AI in their earnings calls, and their stock rallies — even if the actual numbers disappoint. The story is what matters.

As quants, we may be skeptical of this phenomenon and we may dismiss these stories as fairy tales, but the truth is, it’s very hard to make money by betting against the ultimate forces that drive markets. And these forces are stories — not facts, not data. Not many investors will have profited from shorting Theranos or LTCM. Those who did needed a lot of patience and very deep pockets. Stories can outlast the means of even the most accurate quant.

It’s very hard to make money by betting against the ultimate forces that drive markets. And these forces are stories — not facts, not data.

The academic foundation

Our first taste of ‘more data ≠ more informed’ came in the early 2000s, when we started collecting tick-by-tick data. We had high expectations for this project, specifically regarding our correlation analysis. There were two things of which we were certain. The first was that the correlation structure between different markets is far from linear. But modelling that reliably requires a lot of data. When using daily data, ‘a lot of data’ implies ‘a long history.’ But looking far back in time conflicted with the second certainty we had: correlations change over time. High-frequency data seemed like the answer: lots of data without a long history!

It's important to note that we implicitly assumed that market dynamics are the same across timeframes. This is itself a story — and a very popular one among technical analysts in those years. It forms the foundation for viewing price patterns as fractals, described by fractal geometry. And it also underpins the popular assumption that trend indicators proven effective on daily price charts will work just as well when applied to lower-frequency data (such as weekly or monthly prices) or higher-frequency data (such as hourly or 15-minute prices).

Unfortunately, we soon came to the realization that this assumption was incorrect. Market dynamics — including their correlation structure — are not constant, but instead vary across different timeframes. Behavioral finance helped us understand why. So, we stopped searching for a solution in that direction.

This exemplifies the quantitative research approach taught at universities: form a hypothesis, test it on real-life data, and reject it if the data doesn’t fit. Which in cases like these also means: reject the story. If you’d asked me back then about a potential explosion of available data, I’d probably have said it would make it easier to bust false stories. No one actually did ask, but I must admit: I would have been wrong.

Just like I was wrong to think that the number of flat-earthers would drop as information delivered through satellites circling our planet became our daily feed of perception. I completely overlooked the fundamental principle of inflation: an exponentially increasing amount of data diminishes the value of each data point. More data makes it easier — or even necessary — for people to ignore most of it. It encourages people to do their own research on only the data that fits the story they’ve embraced. We all do it — whether it’s flat earth, a 60/40 investment approach, statistical arbitrage, or trend following. We all embrace stories.

More data makes it easier — or even necessary — for people to ignore most of it. It encourages people to do their own research on only the data that fits the story they’ve embraced.

Based on the above, it will be clear why we at Transtrend never applied our trend indicators across a wide range of timeframes. But let’s not kid ourselves: this skilled analytical approach doesn’t make us superior. As quants, we are just as susceptible to stories as anyone else — perhaps even more so, because we love abstraction and tend to be less distracted by ‘messy’ details.

This tendency of ours isn’t new. Around 500 BC, a group of mathematicians called the Pythagoreans believed that all phenomena in the universe could be reduced to whole numbers and their ratios — what we now call rational numbers. They thought irrational numbers couldn’t exist. But then one of them, Hippasus, discovered and irrefutably proved that √2 wasn’t rational. What were they to do? Abandon the story? The Pythagoreans weren’t ready for that. Instead, they decided to keep the discovery secret. And, of course, Hippasus was killed.

Stories without facts

The Pythagoreans clung to their story because rational numbers were foundational to their worldview — almost religious in nature. In this sense, preventing Hippasus from making his discovery public was not so different from the Roman Catholic Church forcing Galileo to recant his heliocentric theory centuries later.

By touching on religion, we enter a differently shaped fact/story domain — yet it’s a relevant one. To understand what drives markets, we must first understand what drives people. And we cannot seriously describe what drives people if we aren’t willing to address religion. Let’s not treat religion as the irrational numbers were once treated!

There are certainly Christians whose faith is rooted in accepting specific biblical accounts as literal facts — such as the sun circling the earth, Noah’s ark saving one pair of every species, Methuselah living to 969 years, Jonah being swallowed by a whale, and Jesus feeding thousands with just five loaves of bread and two fish. Just like there are people who reject Christianity by ‘academically’ rejecting one or more of these facts. But for most Christians, these facts are not taken literally; instead, their faith is grounded in principles such as loving God and loving their neighbor as themselves.

Other religions are not essentially different in this respect. Likewise, most people who aren’t religious still embrace the story of love. Many people of my generation will have seen the film Pretty Woman, which was a huge success. But was it really crucial that she was a Hollywood escort and he a corporate raider trying to acquire a shipbuilding company? What if it had been a railroad company instead? Or are these irrelevant details?

I would say that the story of Pretty Woman is compelling because it touches on, and is recognized as, a universal truth. In essence, this same truth — with completely different ‘facts’ — has been portrayed in many other equally moving films and books. In cartoons, the same story has been told using animals, trees, or even unidentifiable creatures. No, Shrek isn’t real, but the story is.

A true story isn’t a collection of facts. It exists independently of facts — sometimes even despite them. Yet, to tell a story or to present it in a movie, we can only list or display a series of facts. In this sense, facts are just the pixels that paint the story. What these pixels represent is essentially irrelevant; the same pixels can paint a completely different story, and the same story can be painted with different pixels.

Facts are just the pixels that paint the story. What these pixels represent is essentially irrelevant.

Facts exalted above stories

Very often, some of these essentially meaningless pixels — over time — become sanctified by the followers of a story. They turn into tokens or symbols. In everyday romantic life, such tokens might be flowers or jewelry. In religion, they manifest as relics or rituals: attending church twice every Sunday, wearing traditional clothing, or the way a man grows and styles his beard. In law, it’s the elevation of the letter above the spirit. What do all these symbols have in common? They are objectively measurable. And that’s also why we quants are so susceptible to this pattern.

Again, it’s not only in religion that facts — transformed into symbols — are exalted above the story itself. Take one of the most famous Dutch books: ‘Het dagboek van Anne Frank’ (“The diary of Anne Frank”). Most people will know what it’s about; a moving story that should never be forgotten. That’s also why the ‘Achterhuis’, the place where Anne and her family hid, has been preserved as a memorial and museum, visited by countless tourists.

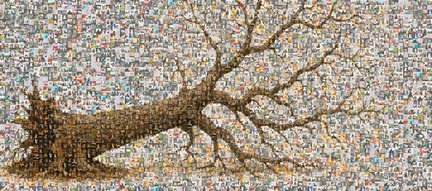

One could argue that the Achterhuis became a symbol of (the horror of) genocide. A few decades ago, it turned out that this status extended to the chestnut tree that grew behind the Achterhuis. Anne mentioned that tree three times in her diary. By 2007, the chestnut tree was in poor condition. Experts advised a controlled removal to prevent a storm from toppling it and damaging the Achterhuis. This proposal sparked emotional protests; opponents reacted as if Anne Frank herself was being deported again. Authorities hesitated to be complicit in such symbolism. I thought I knew what Anne Frank’s diary was about. Suddenly, it seemed to be about a chestnut tree. Until a storm in 2010 ruthlessly ended that story. Or did it merely fell a symbol?

But stories will prevail

This is the world we live in. It’s not just a collection of facts for us quants to measure and analyze, hoping to forecast what is likely to come next. It’s a world driven by people — people who adopt and embrace stories. Facts are necessary as pixels that paint those stories. Some of these pixels are elevated to symbols, worshiped by the followers of the stories. And to reach that status, the facts themselves don’t even have to be true — just look at the Pythagoreans and their devotion to rational numbers.

Successful politicians understand this dynamic. Every now and then, a technocrat emerges, leading a political movement with numbers and quantified facts as their weapons. When I was much younger, fresh out of a technical university, I believed that was the only proper way to lead a country: by facts and numbers. Now I know better. Technocrats don’t lead people — they annoy them. People are led by stories. And the most successful politicians jump on the bandwagon of stories that are already unfolding. We can only hope these stories are mostly factual. But as far as the course of future events is concerned, that makes no difference.

The storm that felled Anne Frank’s chestnut tree wasn’t human. But our economy is. And isn’t that economy — at least, the way we quants look at it — a forest rich in chestnut trees too? Don’t we, time and again, elevate numbers? One moment it’s credit ratings, the next it’s budget deficits, CPIs, or job numbers. Don’t these numbers only have meaning as long as we give them meaning? But what happens when only we quants worship such data? What if the people in our societies — the people who ultimately drive our economies and vote in elections — what if our societies lose faith in these symbols?

What if the people in our societies — the people who ultimately drive our economies and vote in elections — what if our societies lose faith in these symbols?

U.S. President Trump recently declared Chicago ‘the murder capital of the world.’ We quants will never find statistics to support that claim. Similarly, when President Trump claimed he will cut drug prices by 1200, 1300, 1400, 1500 percent, such numbers make no sense from a quantitative perspective. But persistently trying to counter such numbers with ‘better’ numbers is equally pointless. It’s like a chess player explaining the position of the king and the queen to a poker player. They may use the same words, but they talk different symbols.

We quants could dismiss the quantitative skills of President Trump and other political leaders, but that won’t improve our understanding of markets. Maybe we should realize that our facts and numbers are not the cornerstones of our societies — at least, not anymore. This wouldn’t even constitute a radical change. If we look back just a little further than our own academic confirmation, we might realize that we are the offspring of a quant age that lasted barely half a century — a footnote in the hundreds of thousands of years of human civilization united by shared stories.

If stories, not data, drive our societies and drive our markets, why do quantitative investors base their decisions on data? I suppose every investor has different arguments — or, should we say, a different story based on different beliefs. We’ll explain our story in the next part of this series.