Commodity futures as global benchmarks

How “New York” is New York coffee?

How “New York” is New York coffee?

For over 30 years, the United States has been home to some of the largest commodity futures markets in the world. Many of these futures contracts, such as those for gold, crude oil, coffee, and sugar traded in New York, and wheat, corn, and soybeans traded in Chicago, serve as global price benchmarks. This is not a coincidence. The U.S. market for these commodities is part of — and in some cases the center of — the global market for these commodities. However, in recent years, various protective policies have effectively been creating a divide between the local U.S. market and the global market. And this separation could potentially undermine the usefulness of these U.S. futures contracts as global benchmarks.

As a typical example, let’s reread President Trump’s Truth Social message published on 3 March: “To the Great Farmers of the United States: Get ready to start making a lot of agricultural product to be sold INSIDE of the United States. Tariffs will go on external product on April 2nd. Have fun!” This clearly lacks the ambition of selling on the global market. For, let’s say, corn futures traded in Chicago, this isn’t really an issue. U.S. farmers growing corn would of course prefer having the ability to export, as this could potentially offer them higher prices, but with or without export possibilities, Chicago futures prices continue to be a relevant benchmark for them. And for the (remaining) foreign importers of U.S. corn, these continue to be a relevant benchmark as well.

Tariffs on commodities can create a divergence between the price of a futures contract and the spot price of the specific commodity for which the futures contract is used as a benchmark and/or hedging instrument. Their price difference can become dependent more than before on the origin of the physical commodity bought or sold, and/or the agreed-upon delivery place.

In itself, price differences between the futures price and the spot price are not an issue for commercial buyers and sellers who use the futures contract for these purposes. In fact, it’s almost standard for the futures price and the price of the specific commodity bought or sold to be different. Such differences are for instance the result of specific requirements of the buyer with respect to the quality of the commodity to be delivered, or by the agreed-upon place of delivery, which is often different from the cheapest-to-deliver warehouse location that determines the price of the futures contract. Such price differences are known in advance; commercial buyers and sellers take them into account when they enter into a contract of purchase or sale in the physical market. However, it becomes an issue when the futures price and the specific spot price move differently in an unpredictable way.

This risk is called “basis risk”, with the basis referring to the difference between the futures price and the spot price. This constitutes no risk for speculators such as Transtrend, who only trade the futures contracts. But it does constitute a serious risk for commercials who use the futures contract as a benchmark and/or hedging instrument. And for that reason, tariffs can undermine the usefulness of the futures contact.

But being a global benchmark also means that it is used in deals between sellers and buyers who have no intention of delivering or purchasing the commodity in the U.S. Take Arabica coffee, for example. The only coffee produced in the U.S. with some volume is Hawaiian coffee. But Hawaii isn’t on the list of Deliverable Origins for the Coffee C contract traded on the Intercontinental Exchange (ICE Futures U.S., formerly New York Board of Trade (NYBOT)). Despite this, the often-dubbed “New York coffee” serves as the global benchmark for Arabica coffee.

Let’s consider the following (semi-hypothetical) situation. A typical deal between a European coffee roaster and a Brazilian coffee farmer involves the farmer delivering an agreed-upon quality of coffee beans at an agreed-upon time in an agreed-upon harbor in Brazil. The farmer will receive, let’s say, 5 cents above the (benchmark) price traded in New York at the moment of delivery. This coffee will never pass through New York. Imagine the roaster’s dismay if they suddenly would have to pay a 20 percent higher price to the farmer because the coffee price in New York rose 20 percent due to tariffs imposed overnight in the U.S.

It's very likely that the roaster will hedge their agreed-upon purchase through a long position in the coffee futures contract. In that case, this 20 percent tariff-induced price hike will effectively not impact them; at least not for this particular purchase. But what about future deals? To address this, coffee roasters and farmers could modify their purchase agreements to refer to the benchmark price excluding the impact of tariffs. But how large is that impact? If the U.S. would impose a constant 20 percent tariff on imported coffee, there will be no dispute. But if tariffs would vary over time and from country of origin to country of origin, calculating the exact impact on the futures price will be contentious. And traders dislike contentious agreements; that’s precisely why they use mutually accepted benchmarks. Relevant benchmarks.

One key reason why U.S. commodity futures have become global benchmarks is that the U.S. used to be an open market with little to no trade barriers. With tariffs on imported commodities — and even worse, flip-flopping tariffs — U.S. futures contracts on these commodities may no longer serve as relevant and reliable benchmarks for commercials trading these commodities between South America, Africa, Europe, Asia, and Australia. This situation may well force these market participants to change their way of doing business.

With tariffs on imported commodities, U.S. futures contracts on these commodities may no longer serve as relevant and reliable benchmarks for commercials trading these commodities between South America, Africa, Europe, Asia, and Australia.

Let’s return to our coffee example. Currently, the only deliverable coffee that can enter the U.S. tariff-free is Mexican coffee. If the U.S. tariffs announced on 2 April —"Liberation Day” — were truly as disruptive to the international coffee trade as we’ve made it seem, why haven’t we heard concerns from the coffee industry? To understand this, we need to take a closer look at the specifications of the Coffee C contract. The list of Delivery Locations includes not only exchange-licensed warehouses in the Ports of New York District, Virginia, New Orleans, Houston, and Miami, but also Bremen/Hamburg, Antwerp, and Barcelona. That’s in Europe!

In fact, roughly 90 percent of the certified coffee stocks are currently held in EU warehouses. This is not a response to the recent U.S. tariffs; it has been the case for much longer. So, effectively, New York coffee isn’t really New York coffee. While it may be traded in U.S. dollars, on a U.S. exchange, and under U.S. regulatory oversight, the price formation process is “European”, i.e., not affected by U.S. tariffs. And even the coffee delivered against the contracts within the U.S. isn’t necessarily affected by U.S. tariffs because ICE allows delivery to bonded warehouses. These are secure facilities where imported goods are stored without payment of import taxes and duties until the goods are dispatched to their final destination. Such coffee is technically delivered in the U.S., but cannot yet be consumed there.

There is of course a risk that the practice of bonded warehousing may no longer be permitted at some point. But as long as Arabica coffee can enter the EU warehouses duty-free, ICE can continue to define their contract as “the world benchmark for Arabica coffee.” Commercial traders from around the globe can continue to use the contract as a benchmark, just as they’ve done in the past. And when buyers want the coffee delivered in the U.S. outside the bonded warehouses, they can unambiguously extend their purchase agreements to specify which party will pay any imposed tariffs. At the time of delivery, the actual amount of tariffs to be paid on coffee from a specific country of origin will be undisputed.

So, U.S. tariffs on coffee actually pose no concern for the Arabica coffee market because New York coffee isn’t really New York coffee. But what about the various other U.S. commodity futures that are used as global benchmarks?

Another contract whose price is not sensitive to U.S. tariffs is “New York sugar”, officially known as Sugar No. 11, also traded in the U.S. on ICE. In this case, the reason lies in the place of delivery, which is not the place of destination (as it is with coffee), but the country of origin. This is before import tariffs are applied. More precisely, “The contract prices the physical delivery of raw cane sugar, free-on-board the receiver's vessel to a port within the country of origin of the sugar.”

The list of Deliverable Origins includes countries from all continents except Europe. (Europe doesn’t grow sugar cane, only sugar beet, which is deliverable on another futures contract, listed in London.) The list of cane sugar’s countries of origin ranges alphabetically from Argentina to Zimbabwe, which explains why the No. 11 contract is often dubbed “World sugar”. Here also, ICE’s definition of their contract as “the world benchmark for raw sugar trading” seems accurate.

One could argue about the effectiveness of this futures contract in hedging price risks in countries where sugar prices can deviate significantly from the global price due to import/export barriers. But for the U.S. market, this isn’t really an issue. ICE has provided an alternative contract: Sugar No. 16. This contract prices “physical delivery of U.S.-grown (or foreign origin with duty paid by deliverer) raw cane sugar at one of five U.S. refinery ports as selected by the receiver.”

The Sugar No. 16 contract has been listed since 2008, replacing the long-running domestic No. 14 contract. However, it has never been traded very actively, even with the recent threat of tariffs. U.S. sugar traders thus far seem to prefer the larger liquidity of the Sugar No. 11 contract over the lower basis risk of the No. 16 contract.

Most traders will only switch to another benchmark once the majority have already made the switch, making it a classic chicken-and-egg problem.

It’s important to note that habits tend to be remarkably strong among market participants. For instance, it took a lot of persuasion from the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) to make the market switch to the ultra-low sulfur diesel specification as a benchmark for trading heating oil after it was introduced. Of course, most commercial traders preferred the ultra-low sulfur specs because they more closely resembled the diesel they actually traded. But traders have an even stronger preference for a liquid benchmark. So, most traders will only switch to another benchmark once the majority have already made the switch, making it a classic chicken-and-egg problem.

Looking further, it seems that the Coffee C and the Sugar No. 11 futures are exceptions rather than the rule. Most U.S. commodity futures are defined similar to Sugar No. 16, with physical delivery only within the U.S. This applies to the energy futures on the New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX), the precious metals on the Commodity Exchange (COMEX), cocoa and cotton on ICE Futures U.S., and grains, oilseeds, and livestock on CME. The primary reason for this is that these contracts were not intended to be global benchmarks. They were introduced as hedging and price discovery instruments for the U.S. market. Especially the agricultural futures have been very successful in this role for many decades, and most of them continue to be, as we’ve already noted with respect to Chicago corn.

New York coffee was introduced for similar reasons. The European delivery locations of Antwerp, Bremen/Hamburg, and Barcelona were only added after 2000. This expansion can be seen as part of a broader globalization trend that accelerated after the fall of the Berlin Wall. This wasn’t just politics; groundbreaking developments in data and communications (connectivity) also played a crucial role in this trend.

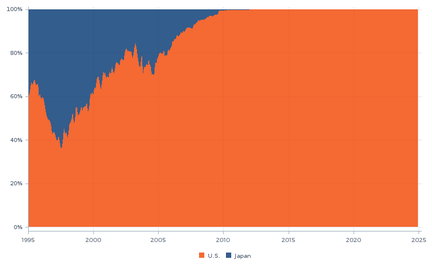

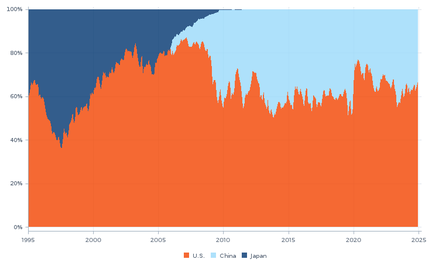

Up until 1995, commodity futures markets were predominantly domestic, and so was their member base. There were almost no brokerage firms offering global access. In addition to U.S. contracts, there were, for instance, various very liquid Japanese commodity futures, among others on coffee, soybeans, and corn. At Transtrend, we traded many of these contracts. To do so, we initially had to use a local Japanese broker, just as we used local brokers to trade commodity futures in Malaysia, the Netherlands, France, England, Canada, and the U.S.

Up until 1995, commodity futures markets were predominantly domestic.

As the globalization trend progressed and trade barriers diminished, local brokers were replaced by brokers offering global access. But in this very same trend, many domestic contracts lost their purpose. For example, the only remaining differences between soybean prices in Japan and the U.S. were location and currency, both of which could be managed more effectively through other means. This was one of the reasons why agricultural futures almost completely disappeared from Japan.

Another factor were the technological advancements necessary to bring the exchanges into the 21st century. The Japanese agricultural futures exchanges lagged in this respect. Some U.S. exchanges, such as NYMEX and the Coffee, Sugar and Cocoa Exchange (CSCE), also lagged, but they were effectively absorbed by the technologically more advanced CME and ICE. These exchanges became the home bases of the global benchmarks that a whole generation of traders grew up with. And that some of us may take for granted.

But meanwhile, things are changing again. The whole trend towards globalization seems more and more like a pendulum swing that by now is past its zenith. One could argue that the turning point occurred already before the Brexit referendum in 2016. Since then, a deglobalization trend has been gaining momentum. Globally, political parties with nationalistic agendas have gained electoral traction, including in continental European countries such as our own. And the raising of trade barriers, not only through tariffs, also fits this deglobalization trend.

Since the popularity of U.S. commodity futures as global benchmarks was a fruit of the globalization trend, it’s not certain that these contracts will retain this status if deglobalization continues. The first cracks are already visible. In which direction might this trend proceed? Will the market revert to predominantly domestic contracts? Or will new or adjusted truly global contracts, such as Coffee C and Sugar No 11, replace the essentially domestic U.S. contracts? Or perhaps a combination of both?

Since the popularity of U.S. commodity futures as global benchmarks was a fruit of the globalization trend, it’s not certain that these contracts will retain this status if deglobalization continues.

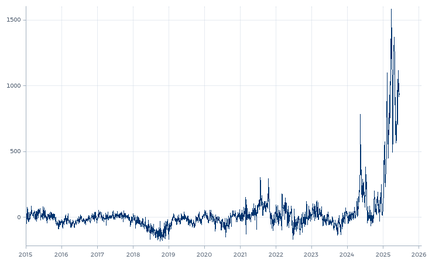

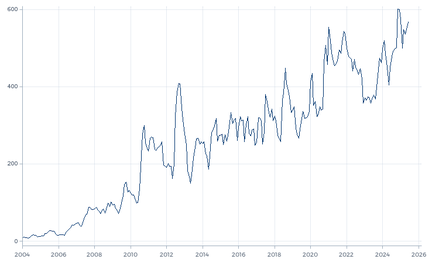

An example of such a crack is the growing dispersion between copper prices within and outside the U.S. as a result of tariffs or the threat thereof in the U.S. This has led to increasing price differences between domestic U.S. High Grade Copper futures traded in New York (on COMEX) and global Copper futures traded in London (on the London Metal Exchange (LME)). In this case, the COMEX contract — with delivery in warehouses in the U.S. only — serves as the most appropriate benchmark for market participants within the U.S. and copper exporters to the U.S., while the LME contract — with delivery in warehouses in the UK, continental Europe, and the U.S. — serves as a better benchmark and hedging instrument for the global copper price.

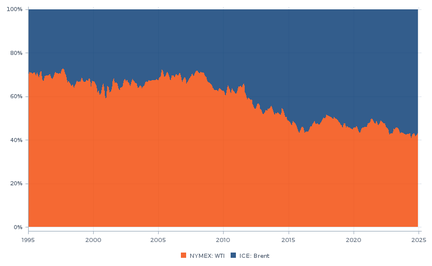

Somewhat comparable, NYMEX’s WTI Crude Oil futures contract — with delivery only in Cushing, Oklahoma — is an adequate benchmark for crude oil prices within the U.S., while ICE’s Brent futures contract — with delivery worldwide — has become the global benchmark. According to ICE, around 75 percent of the world’s traded crude oil is priced relative to Brent. Although Brent is often referred to as “North Sea oil”, the basket of deliverable crudes has recently been expanded to include oil from the U.S.

The decreasing percentage of oil futures traded on NYMEX can be seen as a diminishing acceptance of the domestic U.S. market as a benchmark for the global market. And the growing percentage of oil futures traded on ICE can be seen as a result of the exchange’s ongoing efforts to make these contracts a truly global alternative. This is similar to what ICE did with the Coffee C and Sugar No. 11 futures, and aligns with the amendments that LME made in recent years to make their metal contracts more global.

But if this transition away from domestic U.S. benchmarks is part of an ongoing deglobalization trend, it’s also not certain that this will continue to be accompanied by a growing popularity of the truly global contracts such as Brent. It could also lead to a growing demand for other domestic or regional contracts. China appears to be capitalizing on this development by transforming and opening its futures exchanges, not with the aim of making the listed contracts the new global benchmarks, but to create meaningful, globally accessible benchmarks for the Chinese market, also for many commodities other than oil.

But if this transition away from domestic U.S. benchmarks is part of an ongoing deglobalization trend, it’s also not certain that this will continue to be accompanied by a growing popularity of the truly global contracts.

Chinese futures are being positioned to become the most logical benchmarks for the Chinese market, including for commercial traders transporting commodities into or out of China. Just as domestic U.S. commodity futures are designed to be, and continue to be, the most logical benchmarks for the U.S. market, including for the commercials that export these specific commodities from the U.S.

The grains traded on CME are a good example. These are truly domestic contracts. Not only is the place of delivery limited to warehouses within the U.S., but the grain delivered must also be of U.S. origin. Without trade barriers, this doesn’t result in divergence with global prices. However, in response to the U.S. tariffs imposed earlier this year, prices within and outside the U.S. started to move in different directions.

For commercials trading for instance Brazilian yellow corn, this wasn’t necessarily an issue as long as they didn’t use the CME contract as a benchmark or hedging instrument, but used the cash-settled corn futures contract listed on the Brazilian exchange B3 instead. This contract refers to yellow corn of Brazilian origin. Similarly, it wasn’t an issue for commercials trading European corn or wheat either, as long as they used the corn and milling wheat contracts listed on Euronext Paris, which refer to grains of European origin.

In recent years, these Brazilian and European grain futures have attracted more interest, again indicating a diminishing acceptance of the U.S. contracts as global benchmarks. The grains market seems to be reverting to the situation before globalization, with different domestic contracts for domestic purposes. The recent tariffs unrest did not initiate this turnaround; it had already started earlier, among others fueled by various protectionist measures around the world.

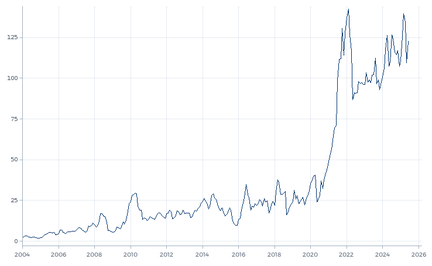

An interesting case is the soybean market. Soybeans are predominantly cultivated for the soybean oil extracted from the beans, which is a popular cooking oil for human consumption. As such, it competes with other vegetable oils like rapeseed oil, sunflower oil, and palm oil. In the U.S., however, soybean oil is also extensively used for biofuel, blended into gasoline and diesel. Not for economic reasons, but because of mandatory levels established in the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) program managed by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

This is a highly political process, as was shown once again on 13 June last when the EPA proposed new standards to lift biofuel volume requirements to the highest level since the RFS program’s introduction. One of the proposals reads: “Puts America first by reducing the value of renewable fuels and feedstocks from foreign countries.” This ambition clearly does not align with any goal for the U.S. to be the center of the global market for soybeans and soybean oil. And therefore, also not with any goal for the CME futures contracts on these commodities to be global benchmarks. Their suitability for functioning as such has been deteriorating for some time already.

To be fair, the U.S. is not the only country that (ab)uses environmental protection arguments to support its farmers. The European Union has its Renewable Energy Directive, which also includes mandatory levels of biofuels to be mixed into traditional fuels. Since its latest update, the EU is phasing out the use of palm oil in biofuels, officially due to concerns about deforestation and indirect land-use change. But it is no coincidence that European farmers don’t grow palm trees. What they do grow is rapeseed, the oil of which happens to be the major feedstock for EU biofuel production. And this cannot be Canadian rapeseed oil, as Canadian farmers grow genetically modified (GMO) varieties, the use of which is restricted in the EU.

So, Malaysia grows and promotes the use of palm oil, and domestic palm oil futures are traded in Malaysia. The EU grows and promotes non-GMO rapeseed, and domestic European rapeseed futures are traded in the EU. Canada grows and promotes canola, and domestic canola futures have always traded in Canada. And the U.S. grows and promotes soybeans, and domestic soybean futures are traded in the U.S.⁴

This could qualify as a neat partitioning of the world in different vegetable oils — comprehensible and workable for everyone involved — if only these four regions were the largest producers of these vegetable oils. But they aren’t. The U.S. is not the world’s largest producer of soybeans; that position is held by Brazil. Additionally, the world’s largest importer of soybeans is China. And the world’s largest transit port for soybeans is Rotterdam.

Suppose a trading house is active in shipping soybeans from Brazil to China. Which soybean futures can it most effectively use in its agreements and for hedging?

Suppose a trading house is active in shipping soybeans from Brazil to China. Which soybean futures can it most effectively use in its agreements and for hedging now that the CME futures are becoming less suitable? One could argue for the South American Soybean futures (free-on-board Santos, Brazil), a contract developed jointly by the CME and B3. But for various reasons, this contract hasn’t gained much interest yet. Meanwhile, at the Chinese end of this shipment, the Soybean Oil and Soybean Meal contracts listed on the Dalian Commodity Exchange in China have become sizable markets, already since 2005. However, the Soybean futures listed there have not seen the same level of interest.

For commercials trading soybeans between South America and China, the most relevant prices are the soybean oil and soybean meal prices in China, and the soybean prices in South America. The CME Soybean futures contract used to be a convenient benchmark for the latter, but since the U.S. is turning inward and away from the world market, the basis risk starts to become a problem. However, the market has not yet gathered around a more suitable alternative. This is a manifestation of the same chicken-and-egg problem we mentioned before: a benchmark has to be accepted to become accepted.

Located in Rotterdam ourselves, we would naturally propose a Rotterdam harbor soybean contract to be listed on Euronext or ICE. Internally, we’ve joked about starting a promotion campaign for such a contract. But this is of course not our role. It’s up to the physical traders to determine which contracts they prefer to use as benchmarks and for hedging purposes. Our role is to support this process by carrying price risk, offering liquidity, and contributing to the price discovery process, wherever the market chooses to make this happen. In this respect, we’re a trend following CTA too. And the current trend in commodity futures is away from domestic U.S. contracts. Either towards truly global contracts or towards other domestic contracts outside the U.S.

¹ U.S. represents the Open Interest in Soybean futures traded in Chicago. Japan represents the aggregate Open Interest in U.S. Soybean futures traded in Osaka and Fukuoka, and Non-GMO U.S. Soybean futures traded in Kansai and Tokyo. Due to lack of data, U.S. Soybean futures traded in Chubu and Kansai have been excluded from the analysis. All Open Interest is first converted to the same weight unit before being compared to each other.

² The peak observed in 2024 was the result of a short squeeze on COMEX.

³ The strong increase in Open Interest observed in 2021 was the result of a strong expansion of the Brazilian corn ethanol industry.

⁴ Canola futures have always traded on the Winnipeg Commodity Exchange (WCE), a commodity futures exchange in Canada. In 2007, WCE was acquired by the U.S.-based Intercontinental Exchange and subsequently rebranded as ICE Futures Canada. In 2018, the canola futures were transitioned to ICE Futures U.S., where they continue to represent Canadian canola to this day.

⁵ U.S. represents the Open Interest in Soybean futures traded in Chicago. China represents the Open Interest in Soybean Oil futures traded in Dalian. This Open Interest is converted to a Soybean equivalent using a 1:0.15 ratio. Japan represents the aggregate Open Interest in U.S. Soybean futures traded in Osaka and Fukuoka, and Non-GMO U.S. Soybean futures traded in Kansai and Tokyo. Due to lack of data, U.S. Soybean futures traded in Chubu and Kansai have been excluded from the analysis. All Open Interest is first converted to the same weight unit before being compared to each other.